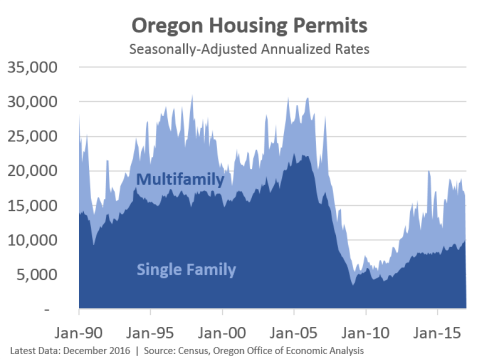

First, permits for new construction continue to increase, albeit slowly. Multifamily permits rebounded first and seem to be holding steady at a relatively high level — somewhat larger than the mid-2000s but not quite as strong as the construction booms in the late 1980s and late 1990s. Single family permits have lagged and are just now about halfway back to 1990s level of construction, let alone peak bubble rates.

Given the nature of the Great Recession — a housing bubble and financial crisis — it wasn’t a huge surprise to see housing lag the recovery, even if it used to be the first thing to bounce back. However in recent years the lack of construction has become a big issue in terms of eroding affordability, which is a national and a statewide problem.

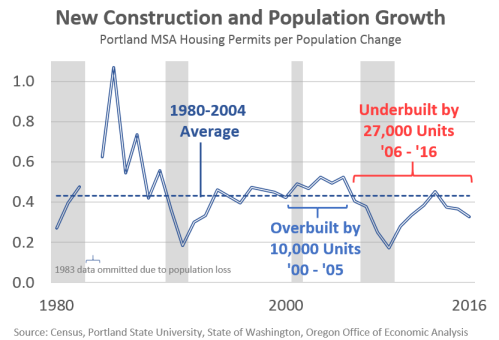

Of course it’s not just that the total number of housing starts is relatively low that’s an issue. The problem is that the level of new construction in the past decade has been considerably less than what is needed to keep pace with a growing population. It’s the lack of supply relative to the growing demand that underlies the affordability challenges. The housing bust has clearly been disproportionate to the boom. The fact we were/are underbuilding was apparent all the way back in 2011. While our office had a more subdued housing outlook than many national forecasters, we still expected starts to increase faster than they have to meet the the actual need and demand in the economy.

Note: While our office’s chart below tracks the Portland region, everywhere else in the state I have looked, the pattern is essentially the same.

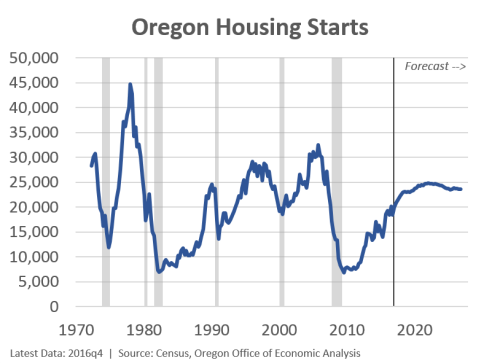

In terms of the outlook, our office still expects housing starts to increase a bit further. As we write in our forecast document:

Over the extended horizon, starts are expected to average a little more than 23,000 per year to meet demand for a larger population and also, partially, to catch-up for the underbuilding that has occurred in recent years. As of today, new home construction in cumulatively about one year behind the stable growth levels of prior decades even after accounting for the overbuilding during the boom.

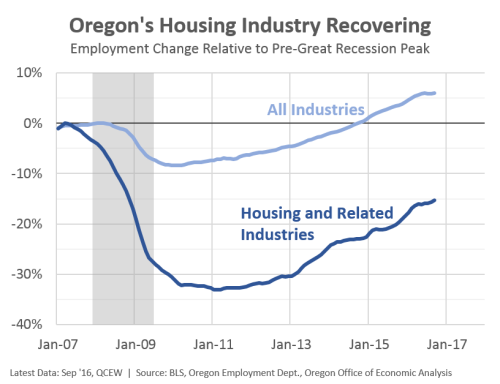

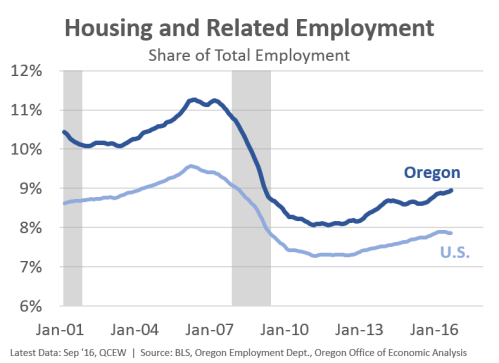

Just as construction activity has yet to recover, construction and related employment remains about 15 percent below pre-Great Recession levels [1].

Such jobs have been growing at an above average pace in recent years, however there remains considerable room left to go in order to return to something approaching historical norms. It should also be noted that housing (and government) jobs represent a larger share of local employment in the state’s secondary metros and rural areas. As the housing market has returned to growth, it has boosted local economies in recent years. This was missing throughout the early stages of recovery in much of the state.

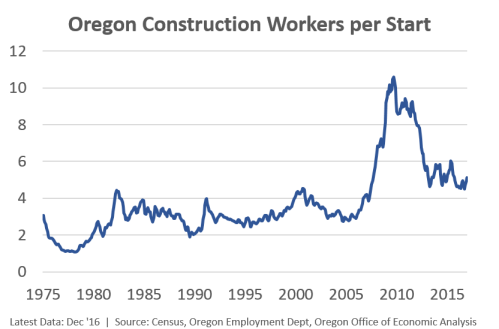

One other interesting trend has been the shift in the number of construction workers per housing start. This ratio remains higher than has historically been the case. Now, I don’t think it means there are literally more individuals working on each home. Rather it is a crude ratio. The shift likely reflects a few different trends, including more multifamily, but also increased remodeling activity which requires workers (and permits) but does not result in a newly build home.

Overall these trends seen in the data are not unique to Oregon. The national data show the same issues. That is both encouraging and discouraging at the same time. On the positive side, it means that local problems are not the main driver behind the housing market issues today. On the bad side, it means there is something impacting the entire national housing market that is driving these results which makes it harder to fix locally. Our office has dug into a number of the supply side constraints in recent months and will summarize that work in the near future. Update: Here is our summary of the main supply constraints.

No comments:

Post a Comment